What drives our long-term behaviors or shapes our worldview? It’s all about identity—the narrative we tell ourselves about who we are. Shaped family, culture, religion, experiences, our self-identity informs our values and beliefs, which influence how we interact and see the world and ourselves. We can design experiences that foster a sense of belonging and connection and provide opportunities for self-expression and personal growth. Doing so can unlock our identities’ potential and create a brighter, more human-centered future.

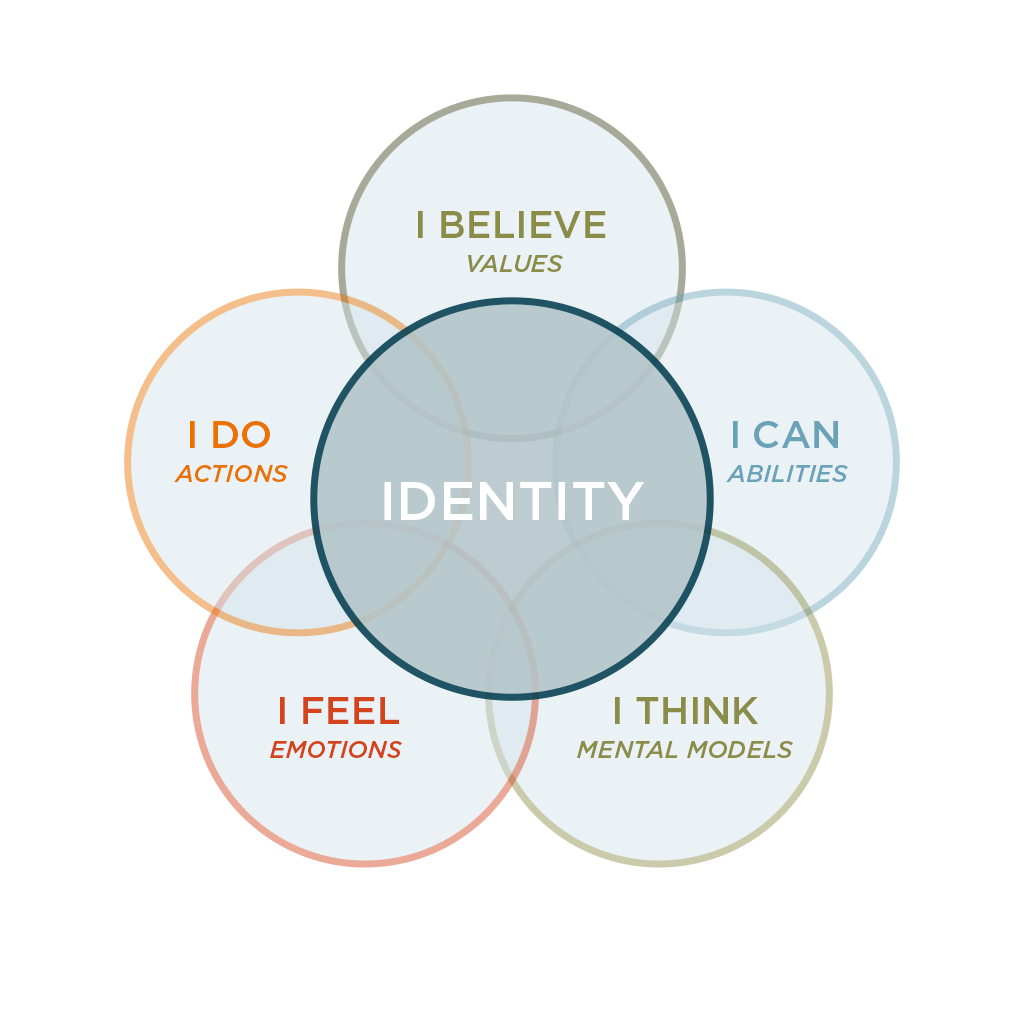

Identity isn’t just a checklist of demographic details; it’s the rich, complex narrative we weave about our sense of self. It encompasses our thoughts, emotions, abilities, and actions—the essence of who we believe we are. For example, a person’s identity might include a sense of pride in their cultural background, a commitment to their religious community, or a passion for their hobbies.

Many of these identity attributes might be the typical elements society deems important. “I’m a 30-something, white male, college educated, living in MN”. These may have varying levels of importance to people. A simple tool to identify key identify attributes is “I” statements. For example:

But to truly grasp someone’s identity, we must look beyond the surface, exploring the personal and social facets that define us. Our identity also comprises our past experiences and influences, our hopes and dreams for the future, and our values and beliefs. It’s shaped by the people we surround ourselves with, the experiences we have, and the decisions we make, so it is dynamic and always evolving.

Identity can be seen through two lenses: personal and social. Our personal identity is shaped by our unique experiences and characteristics, while our social identity reflects how we fit into the wider world. Understanding the relationship between personal and social identity is crucial for designing interventions that resonate more deeply with people.

Understanding the components of personal identity, such as our values, beliefs, and motivations, can help us better design interventions that speak to people on a more personal level. Our social identity, on the other hand, includes how others perceive us and how we are perceived by ourselves. By understanding our social identity, we can better craft interventions that speak to people on a more universal level.

Individuals also have multiple identities. For example, a person can be seen as a responsible leader by co-workers, a jokester by friends, and a sentimental romantic by their partner. These can all be true, yet sometimes they conflict with each other. Understanding that context matters when talking about identity as it shifts depending on situations and contextual factors is critical when designing using identities.

When designing with identity, it’s essential to have guiding principles. Let’s consider the author of this article, Taylor Livalska. Here is some vital information about Taylor’s identity.

Taylor is Rêve’s Vice President of Client Services. He works directly with our clients and their teams to co-create innovative strategies. He is also our resident behavior design expert. When he isn’t leading our clients toward growth, he enjoys being outdoors.

Now that you’ve met Taylor, let’s explore his six fundamental principles and personal examples of designing for identity. These principles can help designers create more personalized experiences and services.

Understanding behavior through the lens of identity can help us to shape and design products and services that are more tailored to the needs of individuals. It also can help us to better understand the motivations and behaviors of individuals, allowing us to make better decisions. When beginning to harness the power of identity in behavior design, consider these questions:

Initially launched in 1986, the anti-littering initiative “Don’t Mess With Texas” wasn’t merely a call to action; it was a rallying cry that tapped deeply into Texan pride and identity. By associating littering with disrespect toward the state of Texas, the campaign invoked a sense of dualism, positioning litterers and non-litterers as two distinct groups, with the latter being true to Texan values.

The campaign messages consistently reinforced that true Texans don’t litter, leveraging social proof and community standards to shape behavior. This consistency in messaging helps individuals align their actions with their identity as proud Texans, fostering a behavior change that feels intrinsic and self-motivated rather than externally imposed.

The campaign featured Texas icons and everyday citizens, demonstrating anti-littering behaviors, not just telling but showing the desired behavior. This approach makes the behavior more tangible and relatable and leverages the influence of admired figures and the power of social norms to encourage compliance.

Still an active campaign to this day, “Don’t Mess With Texas,” is credited with reducing litter on Texas highways by roughly 72%. The campaign’s effectiveness is a testament to the power of aligning behavior change initiatives with core aspects of individual and collective identity, demonstrating how deeply behavior is influenced by how we see ourselves and wish to be seen by others.

Successful design utilizing identity is not just about acknowledging who we are or who we think we are; it’s a vital tool in the arsenal of behavior design. It provides invaluable insights that can guide the creation of more engaging, effective, and meaningful designs. By embracing the dynamic nature of identity, designers can craft experiences that resonate on a deeper level, fostering long-lasting behaviors and profound changes in how we see the world.